Best Practices for Building Agentic AI Systems: What Actually Works in Production

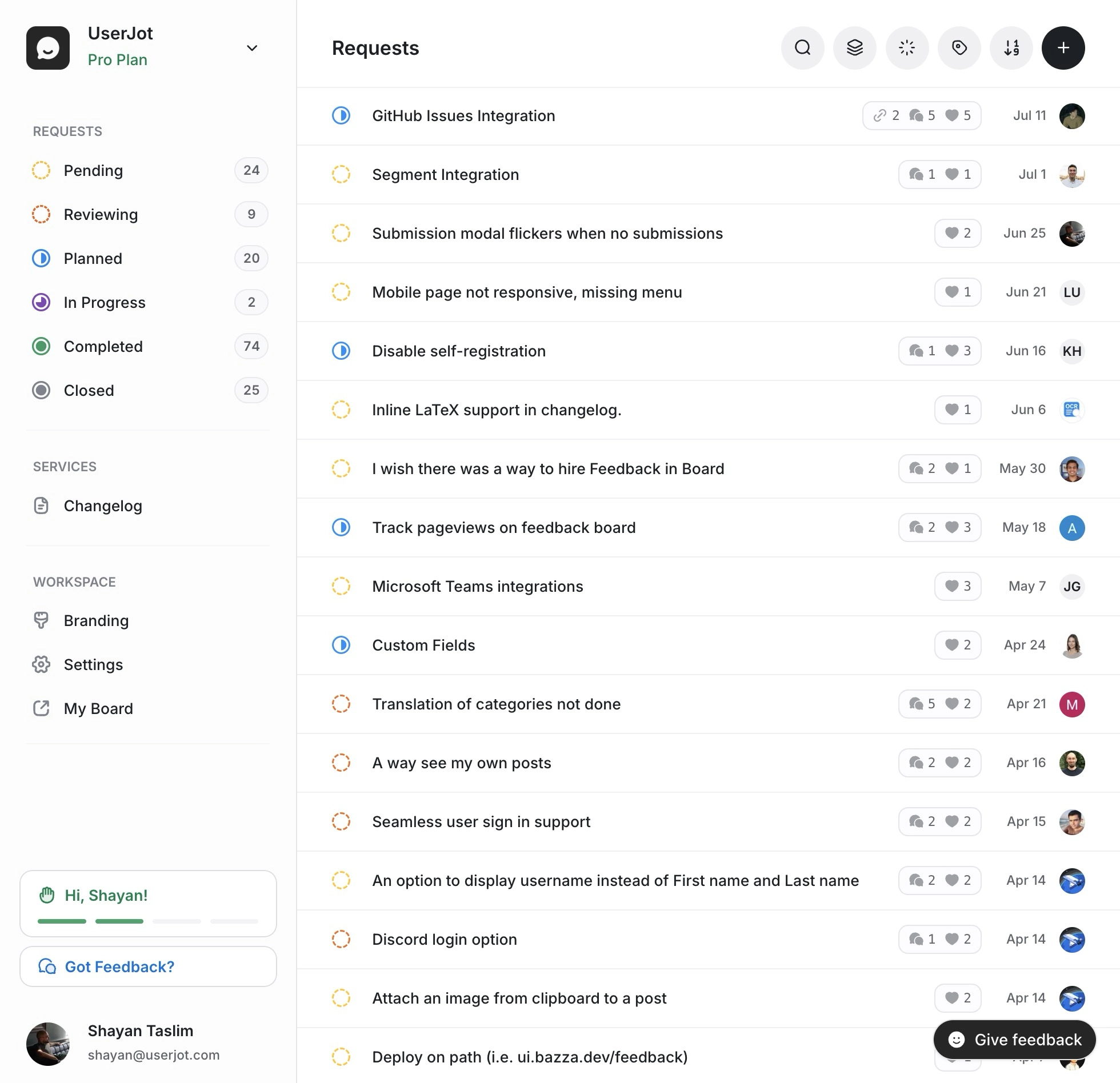

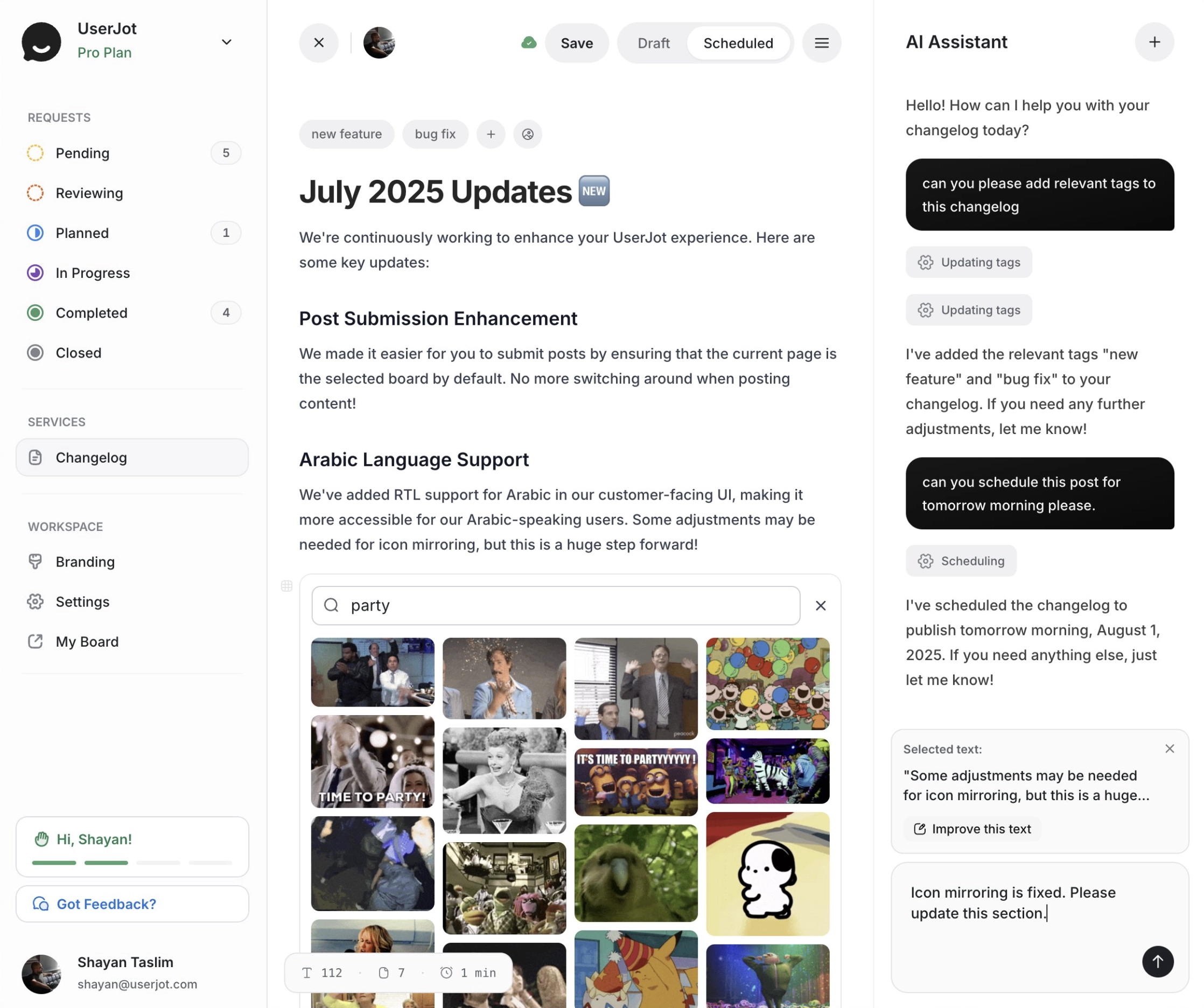

I’ve been experimenting with adding AI agents to UserJot, our feedback, roadmap, and changelog platform. Not the simple “one prompt, one response” stuff. Real agent systems where multiple specialized agents communicate, delegate tasks, and somehow don’t crash into each other.

The goal was to analyze customer feedback at scale, find patterns across hundreds of posts, and auto-generate changelog entries. I spent weeks reverse engineering tools like Gemini CLI and OpenCode, running experiments, breaking things, fixing them, breaking them again. Just pushed a basic version to production as beta, and it’s mostly working.

Here’s what I learned about building agent systems from studying what works in the wild and testing it myself.

The Two-Tier Agent Model That Actually Works

Forget complex hierarchies. You need exactly two levels:

Primary Agents handle the conversation. They understand context, break down tasks, and talk to users. Think of them as project managers who never write code.

Subagents do one thing well. They get a task, complete it, return results. No memory. No context. Just pure function execution.

I tried three-tier systems, four-tier systems, agents talking to agents talking to agents. It all breaks down. Two tiers works best.

Here’s what I landed on:

User → Primary Agent (maintains context)

├─→ Research Agent (finds relevant feedback)

├─→ Analysis Agent (processes sentiment)

└─→ Summary Agent (creates reports)Each subagent runs in complete isolation while the primary agent handles all the orchestration.

Stateless Subagents: The Most Important Rule

Every subagent call should be like calling a pure function with the same input producing the same output, no shared memory, no conversation history, no state.

This sounds limiting until you realize what it gives you:

- Parallel execution: Run 10 subagents at once without them stepping on each other

- Predictable behavior: Same prompt always produces similar results

- Easy testing: Test each agent in isolation

- Simple caching: Cache results by prompt hash

Here’s how I structure subagent communication:

// Primary → Subagent

{

"task": "Analyze sentiment in these 50 feedback items",

"context": "Focus on feature requests about mobile app",

"data": [...],

"constraints": {

"max_processing_time": 5000,

"output_format": "structured_json"

}

}

// Subagent → Primary

{

"status": "complete",

"result": {

"positive": 32,

"negative": 8,

"neutral": 10,

"top_themes": ["navigation", "performance", "offline_mode"]

},

"confidence": 0.92,

"processing_time": 3200

}No conversation history or state, just task in and result out.

Task Decomposition: How to Break Things Down

You’ve got two strategies that work:

Vertical decomposition for sequential tasks:

"Analyze competitor pricing" →

1. Gather pricing pages

2. Extract pricing tiers

3. Calculate per-user costs

4. Compare with our pricingHorizontal decomposition for parallel work:

"Research top 5 competitors" →

├─ Research Competitor A

├─ Research Competitor B

├─ Research Competitor C

├─ Research Competitor D

└─ Research Competitor E

(all run simultaneously)The trick is knowing when to use which: sequential when there are dependencies, parallel when tasks are independent, and you can mix them when needed.

I’m using mixed decomposition for feedback processing:

- Phase 1 (Parallel): Categorize feedback, extract sentiment, identify users

- Phase 2 (Sequential): Group by theme → Prioritize by impact → Generate report

Works every time.

Communication Protocols That Don’t Suck

Your agents need structured communication. Not “please analyze this when you get a chance.” Actual structured protocols.

Every task from primary to subagent needs:

- Clear objective (“Find all feedback mentioning ‘slow loading’”)

- Bounded context (“From the last 30 days”)

- Output specification (“Return as JSON with id, text, user fields”)

- Constraints (“Max 100 results, timeout after 5 seconds”)

Every response from subagent to primary needs:

- Status (complete/partial/failed)

- Result (the actual data)

- Metadata (processing time, confidence, decisions made)

- Recommendations (follow-up tasks, warnings, limitations)

Everything uses structured data exchange with clear specifications.

Agent Specialization Patterns

After studying OpenCode and other systems, I’ve found three ways to specialize agents that make sense:

By capability: Research agents find stuff. Analysis agents process it. Creative agents generate content. Validation agents check quality.

By domain: Legal agents understand contracts. Financial agents handle numbers. Technical agents read code.

By model: Fast agents use Haiku for quick responses. Deep agents use Opus for complex reasoning. Multimodal agents handle images.

Don’t over-specialize. I started with 15 different agent types but now I have 6, each doing one thing really well.

Orchestration Patterns We Actually Use

Here are the four patterns that handle 95% of cases:

Sequential Pipeline

Each output feeds the next input. Good for multi-step processes.

Agent A → Agent B → Agent C → ResultI use this for report generation: gather data → analyze → format → deliver.

MapReduce Pattern

Split work across multiple agents, combine results. Good for large-scale analysis.

┌→ Agent 1 ─┐

Input ─┼→ Agent 2 ─┼→ Reducer → Result

└→ Agent 3 ─┘This is my go-to for feedback analysis in UserJot. When someone’s feedback board gets hundreds of posts (happens more than you’d think), I split them across 10 agents, each processes 100, then combine results. It takes 30 seconds instead of 5 minutes, giving users instant insights about what their customers actually want.

Consensus Pattern

Multiple agents solve the same problem, compare answers. Good for critical decisions.

┌→ Agent 1 ─┐

Task ─┼→ Agent 2 ─┼→ Voting/Merge → Result

└→ Agent 3 ─┘I use this for sentiment analysis on important feedback. Three agents analyze independently, then we take the majority vote, which catches edge cases single agents miss.

Hierarchical Delegation

Primary delegates to subagents, which can delegate to sub-subagents. Good for complex domains.

Primary Agent

├─ Subagent A

│ ├─ Sub-subagent A1

│ └─ Sub-subagent A2

└─ Subagent BHonestly, I rarely use this. It sounds good in theory but becomes a debugging nightmare in practice, so stick to two levels max.

In my beta version, I mostly use MapReduce for feedback analysis and Sequential for report generation. The fancy stuff rarely gets used.

Context Management Without the Mess

How much context should subagents get? Less than you think.

Level 1: Complete Isolation: Subagent gets only the specific task. Use this 80% of the time.

Level 2: Filtered Context: Subagent gets curated relevant background. Use when task needs some history.

Level 3: Windowed Context: Subagent gets last N messages. Use sparingly, usually breaks things.

I pass context three ways:

# Explicit summary

"Previous analysis found 3 critical bugs. Now check if they're fixed in v2.1"

# Structured context

{

"background": "Analyzing Q3 feedback",

"previous_findings": ["slow_loading", "login_issues"],

"current_task": "Find related issues in Q4"

}

# Reference passing

"Analyze document_xyz for quality issues"

# Subagent fetches document independentlyLess context = more predictable behavior.

Error Handling That Actually Handles Errors

Agents fail frequently, so here’s how I handle it:

Graceful degradation chain:

- Subagent fails → Primary agent attempts task

- Still fails → Try different subagent

- Still fails → Return partial results

- Still fails → Ask user for clarification

Retry strategies that work:

- Immediate retry for network failures

- Retry with rephrased prompt for unclear tasks

- Retry with different model for capability issues

- Exponential backoff for rate limits

Failure communication:

{

"status": "failed",

"error_type": "timeout",

"partial_result": {

"processed": 45,

"total": 100

},

"suggested_action": "retry_with_smaller_batch"

}Always return something useful, even when failing.

Performance Optimization Without Overthinking

Model selection: Simple tasks get Haiku. Complex reasoning gets Sonnet. Critical analysis gets Opus. Don’t use Opus for everything.

Parallel execution: Identify independent tasks. Launch them simultaneously. I regularly run 5-10 agents in parallel.

Caching: Cache by prompt hash. Invalidate after 1 hour for dynamic content, 24 hours for static. Saves 40% of API calls.

Batching: Process 50 feedback items in one agent call instead of 50 separate calls. Obvious but often missed.

Monitoring: What to Actually Track

Track these four things:

- Task success rate (are agents completing tasks?)

- Response quality (confidence scores, validation rates)

- Performance (latency, token usage, cost)

- Error patterns (what’s failing and why?)

Here’s my execution trace format:

Primary Agent Start [12:34:56]

├─ Feedback Analyzer Called

│ ├─ Time: 2.3s

│ ├─ Tokens: 1,250

│ └─ Status: Success

├─ Sentiment Processor Called

│ ├─ Time: 1.8s

│ ├─ Tokens: 890

│ └─ Status: Success

└─ Total Time: 4.5s, Total Cost: $0.03Keep it simple, readable, and actionable.

What I Learned Building This at UserJot

I’ve been testing this architecture with real feedback data from our feedback boards. Everything from feature requests to bug reports to “wouldn’t it be cool if” posts. Here’s what surprised me:

Stateless is non-negotiable. Every time I added state “just this once,” things broke within days.

Two tiers is enough. I tried complex hierarchies. They added complexity without adding value.

Most tasks need simple agents. 90% of my agent calls use the simplest, fastest models.

Explicit beats implicit. Clear task definitions. Structured responses. No magic.

Parallel execution changes everything. Running 10 agents simultaneously turned 5-minute tasks into 30-second tasks.

The Principles That Matter

After experimenting with this system and getting it to beta, here are the principles that actually matter:

- Stateless by default: Subagents are pure functions

- Clear boundaries: Explicit task definitions and success criteria

- Fail fast: Quick failure detection and recovery

- Observable execution: Track everything, understand what’s happening

- Composable design: Small, focused agents that combine well

Common Pitfalls I Hit (So You Don’t Have To)

The “Smart Agent” Trap: I tried making agents that could “figure out” what to do. They couldn’t. Be explicit.

The State Creep: “Just this one piece of state.” Then another. Then another. Then everything breaks.

The Deep Hierarchy: Four levels of agents seemed logical. It was a debugging nightmare.

The Context Explosion: Passing entire conversation history to every agent. Tokens aren’t free.

The Perfect Agent: Trying to handle every edge case in one agent. Just make more specialized agents.

Actually Implementing This

Start simple with one primary agent and two subagents, get that working, then add agents as needed rather than just because you can.

Build monitoring from day one. You’ll need it.

Test subagents in isolation. If they need context to work, they’re not isolated enough.

Cache aggressively. Same prompt = same response = why call the API twice?

And remember: agents are tools, not magic. They’re really good at specific tasks but terrible at figuring out what those tasks should be, which is your job.

Stop guessing what to build. Let your users vote.

Try UserJot freeP.S. If you’re curious about how we’re using these patterns to analyze user feedback at scale, UserJot has a free plan. The agent features are still in beta, but the core feedback/roadmap/changelog stuff is rock solid. We eat our own dog food. All our product decisions come from patterns these agents find in our feedback.

FAQ

What’s the minimum viable agent system?

One primary agent that maintains context, one subagent that does actual work. Start there and add complexity only when needed.

Should subagents really have zero memory?

Yes. When you add memory, you add state, and when you add state, you add bugs, so keep them stateless.

How do you handle rate limits with parallel agents?

Implement a token bucket rate limiter to launch agents up to your limit, queue the rest, and process queued tasks as tokens become available.

What’s the best model for primary agents vs subagents?

Primary agents need reasoning ability, so use Sonnet or Opus, while subagents doing simple tasks can use Haiku. Match model to task complexity.

How do you test agent systems?

Test subagents with fixed inputs and expected outputs, orchestration with mocked subagent responses, and the full system with real but limited data.

Can agents call other agents directly?

They can, but shouldn’t. All communication should go through the primary agent to maintain control and visibility.

What about agents that need to maintain conversation state?

That’s the primary agent’s job. It maintains state and passes relevant context to stateless subagents as needed.

How do you handle long-running agent tasks?

Break them into smaller chunks since no agent task should run longer than 30 seconds. If it does, it needs to be decomposed further.

What’s the typical latency for multi-agent operations?

With parallel execution, most operations take 2 to 5 seconds, sequential operations add 1 to 2 seconds per step, and cache hits are near-instant.

Is this architecture overkill for simple use cases?

Yes. If you just need one API call with a prompt, use that instead. This architecture is for when you need multiple specialized agents working together.